- Warsaw, Cracow 2023

- 230 x 310 mm, hardback

- 508 pages, 513 illustrations

Published in collaboration by:

- Museum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów, Warsaw, ISBN 978-83-66104-99-0

- Wawel Royal Castle – State Art Collection, Cracow, ISBN 978-83-66648-61-6

- IRSA Foundation for the Promotion of Culture, Cracow, ISBN 978-83-89831-46-0

Translated from the Polish by Nicholas Hodge and Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz.

The English translation was made possible by a grant from the Lanckoroński Foundation.

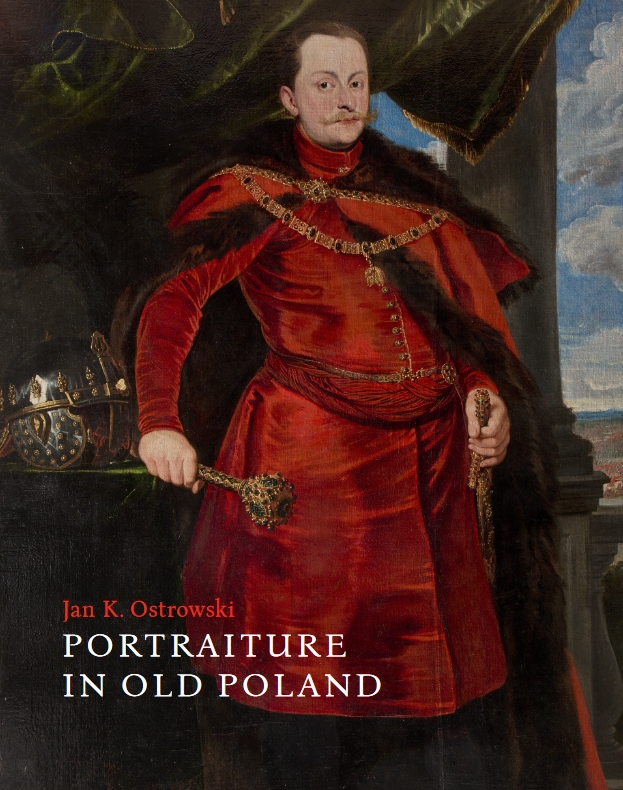

This landmark book is the first English-language study to tackle its subject in depth. Written by one of Poland’s foremost art historians, it is an essential text for readers keen to look beyond the Western European art centres that have dominated art history since the inception of the discipline.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – in spite of its flaws – was once the largest state in Europe, and it produced a distinctive culture that was often at odds with those of the absolutist monarchies of the day. The author casts his net wide, considering both forms of portraiture that were widespread across the continent yet also indigenous specialities such as coffin portraits and tomb banners. He likewise demonstrates how the 18th-century Partitions of Poland affected portraiture and national identity.

The book serves as an incisive exploration of the subject, yet also as a thought-provoking and at times witty resource on how to approach art in general, with the author spotlighting several pitfalls that can mislead the researcher. Finally, he shows how context and rational deduction can help solve iconographic puzzles. The multi-faceted approach means that the book is arguably unique in international literature on the subject.

Jan K. Ostrowski (b. 1947) grew up surrounded by family portraits at home, which sparked a fascination that stayed with him for life. He studied at Cracow’s Jagiellonian University and the University of Nancy. Later, he was a visiting scholar in Florence, Munich, and at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. He taught History of Art at the Jagiellonian University from 1973 to 2018, becoming a full professor in 1992. In 1989 he was appointed director of Wawel Royal Castle in Cracow and he held this post for three decades. Since 2018, he has been president of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. He conceived and directed a programme of inventorying historic sites in the Lviv region (western Ukraine; 23 vols, 1993–2015). He has extensively researched and published on Late Baroque Sculpture in Lviv (Johann Georg Pinsel), Polish Romantic Painting (Piotr Michałowski), and Baroque Painting in Flanders and Italy (Anthony van Dyck, Sinibaldo Scorza). He has been decorated both at home and abroad, including with the Order of Polonia Restituta and France’s Legion of Honour.

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION

PREFACE TO THE POLISH EDITION

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Scope, Methodology, and Structure

1.2. The State of Research

1.3. What Is Portraiture?

2. PATHS TO THE EARLY MODERN INDEPENDENT PORTRAIT

2.1. Funerary Sculpture

2.2. Quasi-portraits and Portraits as Parts of Works of Medieval and Early Modern Art

2.2.1. Adoring Figures

2.2.2. Crypto-portraits and Assisting Figures

2.3. Painted Likenesses of the Deceased as Elements of Commemorative Artworks

2.3.1. Tomb Banners

2.3.2. Coffin Portraits and Portraits on Memorial Tablets

2.3.3. Images of the Dead on Beds of State and Catafalques

3. A SHORT HISTORY OF PORTRAITURE IN OLD POLAND

3.1. Beginnings

3.2. Portraiture in the 17th and 18th Centuries (with Echoes up to the 20th Century)

3.2.1. Typology and Iconography

3.2.2. Style

3.2.3. Analogies

4. THE PORTRAIT IN SOCIETY: FUNCTION AND RECEPTION

4.1. The Circumstances in which Portraits Were Created in Old Poland

4.2. Ways of Exhibiting Portraits

4.3. Portrait Galleries

4.4. A Refl ection of Collective and Individual Life

5. ATTIRE, ATTRIBUTES, AND FURNISHINGS IN PORTRAITS: WHAT OBJECTS TELL US ABOUT THE SITTER AND THEIR TIME

5.1. Regalia

5.2. Costume

5.2.1. The Development and Domination of National Dress (c. 1560/1600–1730/1750)

5.2.2. Two Nations: Polish and German (c. 1750–1795)

5.2.3. National Dress Between Peripheral Lingering and an Elite Renaissance (c. 1800–1939)

5.2.4. Civil Uniforms

5.2.4.1. Order Uniforms

5.2.4.2. Voivodeship Uniforms

5.2.4.3. Solidarity Uniforms

5.2.4.4. Uniforms of the Governing Commission of the Duchy of Warsaw

5.2.4.5. Citizens’ Uniforms of 1809

5.2.4.6. Senators’ Uniforms of the Kingdom of Poland

5.2.4.7. Court and Offi cial Uniforms in the Kingdom of Poland

5.2.4.8. Uniforms of the Governing Bodies and Services of the Republic of Cracow

5.2.4.9. Uniforms of the Estates of Galicia

5.2.4.10. Uniforms of the Estates of the Grand Duchy of Posen (Poznań)

5.2.4.11. School and University Uniforms in the Kingdom of Poland, the ‘Stolen Lands’, and the Republic of Cracow

5.2.5. Women’s Clothing

5.3. Armour

5.4. The Sabre

5.5. Insignia and Attributes of Power

5.5.1. Introduction

5.5.2. Attributes Denoting Military Rank

5.5.3. Attributes of Civil Offices

5.6. Orders and Similar Distinctions

5.7. Attire and Attributes of the Clergy

CONCLUSION

GLOSSARY

ABBREVIATIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX OF NAMES

LIST OF FIGURES

Bibliography to the book is available here.

Orders can be placed via email irsa@irsa.com.pl.